…or rather How to Find the Possibility of Marginalia in Printed Books to Which You Do Not Have Access! If you don’t happen to live or work in the region of a rare books repository, you may be able to get leads about the existence and sometimes nature of marginalia from library catalogues. First, we need the catalogue to have a field for notes about the particular copy. Copy-specific notes can include information about provenance and history (such as re-binding, repair, etc.), and can also include a brief description or transcription of manuscript additions, such as ownership claims, prices, gift inscriptions, and marginalia. These catalogue notes will not be exhaustive, but a book with marginalia in it is likely to have something recorded in that field that might lead us to believe there is material there for us. Most library catalogues (including my own institution’s) do not have a field that includes such notes, but many rare books library catalogues do: this blog post focusses on the catalogues of the Folger Shakespeare Library and the libraries of Oxford University and mentions those of the Newberry and the Huntington.

Library catalogues that include copy-specific notes tend to be customized to the needs of the collections. The way that they record marginalia or other supplements to printed books that we might be interested in differs from library to library and even from cataloguer to cataloguer. You can always start by talking or writing to a librarian for advice: I learned the basics from Georgianna Ziegler at the Folger Shakespeare Library. (Dr. Ziegler is now retired but is still very active as a scholar: “Little Books, Big Gifts: The Artistry of Esther Inglis” is her latest project).

I’m going to start with the Folger Shakespeare Library, as I’m most familiar with it. I’ve gone to the Folger Library’s site, then to “Research” on the top nav bar; from the drop-down menu you can go to “Search the Catalog.” Once there, I select “Advanced Search” from the bottom line of text. This option which will allow me to search multiple fields, connected by Boolean operators such as “and” or “not.” I’ve built a search that is shown in the image below which asks for items that fulfill the following criteria: one, they include the word “health” in the title; two, the title does NOT include the term “electronic resource” (for those of you who use Early English Books Online, you’ll know that the works in EEBO are included within the catalogues of institutions that subscribe to the resource); and three, under “Date type,” I’ve restricted my results to items that “published/created” in a “specific time period” between 1600 and 1620. You can do this search yourself to follow along.

We have some results here! 16 titles, some of which are represented in multiple copies in the Folger’s collection. This is a manageable number for me to sift through; in each entry, I’ll be looking at the “Folger-specific notes.” The first title on the list (The hauen of health : chiefly made for the comfort of students, and consequently for all those that haue a care of their health, amplified vpon fiue words of Hippocrates, written Epid. 6. Labour, meat, drinke, sleepe, Venus: by Thomas Cogan, Master of Artes, and Bacheler of Physicke: and now of late corrected and augmented. Hereunto is added a preseruation from the pestilence: with a short censure of the late sicknesse at Oxford.) is represented in three copies in the Folger’s collection. Each of these copies has a Folger-specific note in the catalogue record.

The notes for the Folger copies of The hauen of health tell us that there are provenance notes in the first copy, which may or may not interest us (provenance refers to the history of ownership of the item). The key for marginalia hunters is the term “manuscript notes,” which can be abbreviated as “ms notes.” For copies two and three, we see that there are manuscript notes in the books. These might or might not be marginalia that interests you; we can’t tell from the catalogue. This is when you might place a request in BookMark: the call number, the title, and your confidence the book might have marginalia in it are all you need. Your correspondent – the person who fields the request through BookMark on the basis that they have access to the Folger’s collections – will request the book be made available to them in the reading room, look through it for marginalia, photograph the marginalia, and send the photos to you by email or file transfer service. That’s it.

Most rare books library catalogues will have a searchable field for the copy-specific notes. Here’s another example. The Oxford Universities catalogue includes rare book holdings in college libraries and in the Bodleian Library. Excluding electronic copies is different than in the Folger catalogue. In SOLO, on the left nav bar, there is a set of filters including “resource type.” If you select “physical resources” and then apply the filter, you will exclude electronic versions. Our search is for “health” in the title, and a publication date between 1600-1620, inclusive. The search results list 13 items, some of which are available in multiple copies.

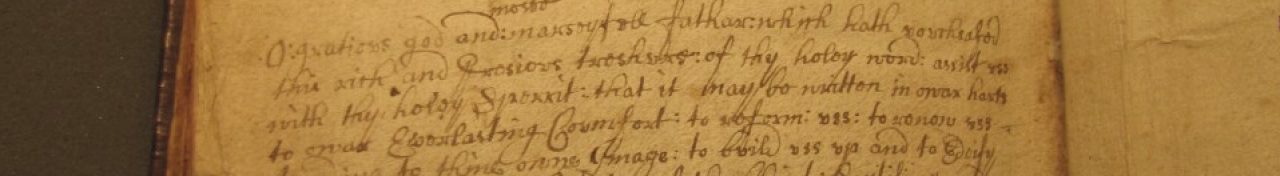

SOLO aggregates the library catalogues of all the Oxford College and University libraries. If we open the record for this title, The treasurie of hidden secrets (1600), we see there are two copies in the system, both at St. John’s College. Both of these items have extensive notes, some in “Provenance Notes” and some in “MS additions.” Here’s a screenshot of the catalogue entry for the second copy at St. John’s, which includes an “MS addition” in the form of a “contents” list (probably a list of the contents of the book, but possibly an inventory of other kinds of materials or objects) <Figure 3>. In addition, the provenance note includes citation of some marginalia that expresses not just the ownership and transmission record normally belonging to provenance, but a set of interpersonal relationships of some emotional magnitude. As with the examples above, you could put in a request through BookMark for a fellow scholar who has access to St. John’s College and can take photographs for you.

Library catalogues are all different, and many don’t have copy-specific notes. I’ve looked at the catalogs for the Newberry (in Chicago) and the Houghton (at Harvard), and they do have a notes field, but it seems to be used mainly for bibliographical observations about the contents and construction of that copy of the book. The Huntington Library catalogue has a category called “Huntington notes” which can include description of marginalia: for instance, for the collection’s 1605 copy of The hauen of health, for example, the Huntington note includes reference to three seventeenth-century ownership claims, two of which are women who share a surname, and for the library’s 1617 copy of Regimen sanitatis Salerni, the note says that the book bears the signature of owner William Newman, with the date 1621. It is possible that these books – and books that are catalogued but lack notes such as these – contain other early modern marginalia, and it might be worth checking out.

At EMMRN, we’re happy to receive requests for photos of marginalia that just have the repository, title, date of publication, and call number. These will be passed on to whomsoever commits to fulfill the request; if you haven’t specified particular marginalia in the request, the fulfiller will look through the copy of the book and take photos of all the marginalia that are in the book, or the type (ownership, gift, notes on the text, miscellaneous additions, etc.) that you would like to retrieve. We’re also happy to answer questions (emmrn@uwaterloo.ca) about how to do this research – and Librarians at libraries will also be preternaturally helpful, in my experience, when we ask them to teach us things we can go on to do ourselves.

Good luck and happy hunting! Drop us a line at emmrn@uwaterloo.ca if you find something interesting or would like to write a blog post about your marginalia adventures.

![Gometius Pereira, Antoniana margarita. [Medina del Campo] 1554. Portion of the front flyleaf with marginalia by S. T. Coleridge.](https://i0.wp.com/earlymodernmarginaliaresearchnetwork.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Screen-Shot-2023-08-17-at-3.22.22-PM.png?resize=640%2C240&ssl=1)